|

The Golden Ass is simultaneously a blend

of erotic adventure, romantic comedy, and religious fable, it is

one of the truly seminal works of early European literature, with

a distinctly Eastern flavouring and a very modern feel. There are

very few works with the pleasurable impact of the Golden Ass.

Apuleius's images retain their vitality from almost 2000 years ago,

losing nothing of their colour and magic. Indeed, the promise of the

closing words of the Prologue: Lector, intende: laetaberis

- 'Lend me your ear, reader: you shall enjoy yourself' are amply

fulfilled. Over the centuries, the Golden Ass has brought pleasure

and inspiration to generations of readers and writers, from

Shakespeare

to

Salman Rushdie.

A copy of the Golden Ass was one of the few things

T.E. Lawrence

('of Arabia')

carried in his saddle-bags throughout the Arab Revolt.

The charge to the reader: intende (lit. 'be attentive') -- rather like the beginning of the first English epic Beowulf : Hwaet ('listen') -- is a much more demanding commencement than 'once upon a time...' It requests the reader to be an active participant in experiencing the tale, not simply a passive listerner (Apuleius's style throughout is consistent with this notion). The Latin statement, in fact, is a conditional: 'if you are attentive, then you shall take pleasure', suggesting that the reader's enjoyment depends upon the degree of attention paid to the tale. The modernity of The Golden Ass originates from the timelessness of the text. This is true of the humour--what we found amusing two thousands years ago we still do today--but also of the non-comic aspect of the work: the continual struggle of individuals to come to grips with and function in a largely unintelligible world. The transformation of man into ass provides a well-lit stage for the drama of this struggle to play upon; his form of an ass allows the narrator a unique vantagepoint from which he is able to better gather together the threads of the mundane world to weave his fantastic tale. But the story remains that of man and his place in the world. This is not to say that Apuleius was not a believer in magic--he had been initiated into the mysteries of Isis and is reputed to have himself performed miracles necessitating the mastery of magic and sorcery. However, The Golden Ass is not a story about magic, the supernatural of the novel is a convience subordinate to the spinning of a story about man and the struggle of life in a world of limited resources. Magic in The Golden Ass may change a man to an ass, but it does not transform the Finite into the Infinite:-- it does not eliminate the 'need' for slaves, make all of the poor men rich or all the hungry satiated. Magic forms part of Apuleius's natural world:-- the world in which it is winter during those months in which Ceres's daughter dwells in Hades; a world in which the earth is not always bountious, not matter how much one propriates the Gods with burnt offerings and other sacrifices. Spells and witchcraft do not change these facts. |

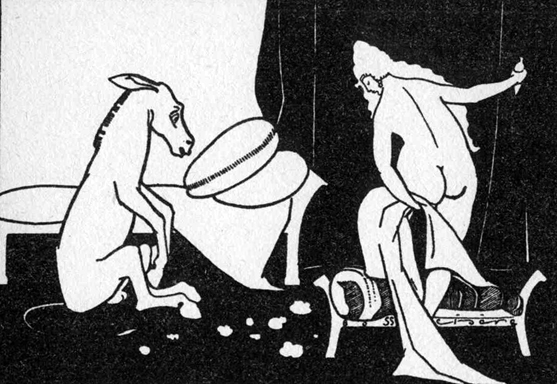

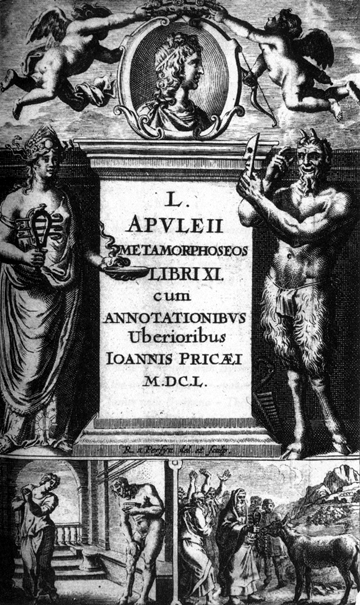

The Golden Ass - frontispiece illustration by Percival Goodman

|

|

Part of the inherent struggle depicted in The Golden Ass

is that of arises from man's own inner desires for pleasure. In this

we find one of the 'Eastern' elements of Apuleius's work, the journey

to escape from the bonds of desire endured by Lucius is similar to the

Hindu

concept of moksha ("release"), the

Bhagavad-Gita

dialogue between Arjuna and Krishna being an excellent

expression of this philosophy. This is not to say that the Golden

Ass is by any means a moralistic tale of a libertine who realises

the 'ungodliness' of his ways and reforms in order to secure a seat

in the heavens. Apuleius celebrates the sensual aspects of life and

his vivacious descriptions of erotic scenes illustrate his possession

of the 'cavalier-poet' virtue of living life to the fullest, both

the pleasurable and the painful. Just as there is a Tantric school

of Hinduism which does not strive to avoid the sensuous side of experience,

Apuleius's is a tale of maturation and the attainment of the wisdom

needed to survive one's desires.

|

|

Apuleius's novel has inspired many subsequent writers and artists and been one of the greatest influences in Western literature, including such classic works as Boccaccio's Decameron, Cervantes's Don Quixote and Swift's Gulliver's Travels. In these there obviously exists the same satyrical style as in the Golden Ass, the same basic image of human madness and endeavour. As well, the bathetic form of the Golden Ass occurs (as well as in the above works) also in Sterne's Tristram Shandy (which, along with Richardson's Clarissa, are considered the first modern novels) and Joyce's famous Ulysses (a sort of 'retelling' the tale of Homer's Odyssey, re-set in 19th century Dublin). In more modern literature, the little known, but very important work of Anglo-Indian novelist G.V. Desani's All About H. Hatterr also carries on Apuleius's mad, bathetic style of story-weaving. More well-known Booker-Award winning Anglo-Indian author Salman Rushdie too writes very much in the Apuleian style--both in the sense of bathos as well as adapting Apuleius's particular manner of interweaving 'mirroring' stories together (see below). In addition to style, an episode in Rushdie's (in)famous novel, The Satanic Verses, displays a thematic borrowing, in that it involves a transformation of the protagonist into bestial form and his subsequent attempts to regain human form:--'[the Golden Ass] serving as the central intertext [of Satanic Verses]', in the words of Dr. Margareta Petersson. The shape-changing theme also occurs in Kafka's Die Verwandlung (The Metamorphosis). This theme, while obviously ubiquitous in human imagination, is unusual in Apuleius in that a first-person narrative is provided by the metamorphed man, as in Kafka. Kafka's novel owes something to the Golden Ass in its plot of an ordinary person who one day suddenly finds himself in a shape not his own--a repulsive shape; and in the protagonist's struggle to survive with his humanity intact. The 'Chinese-box' structure of the Golden Ass (e.g. the stories set within the frame of the primary narrative of Lucius)--similar to the pattern of One Thousand and One Arabian Nights --is perhaps a remnant of the Indo-European epic tradition (and the Greek tradition in particular), which often exhibits the imbedding of tales and myths not structurally part of the main narrative. The majority, if not all, of these interwoven 'mini-stories' are not original to Apuleius; rather, they were well-known tales and anecdotes belonging to the common community--thus Apuleius's introductionary description of his work as ' At ego tibi sermone isto Milesio varias fabulas conseram auresque tuas benivolas lepido susurro permulceam' ["What I should like to do is to weave together different tales in this Milesian mode of story-telling and to stroke your approving ears with some elegant whispers" (Walsh trans. 1)]. Milesian tales are a sort of light entertainment; there existed a large repertoire of such popular myths and anecdotes, though Apuleius--as always--presents them in his unique style. As E.J. Kenney points out, there exists a paradox in Apuleius's preface. He begins by stating that he is going to string together a number of light tales, but then at the end of the introduction he says 'It is a Grecian story I am about to begin' ('Fabulam Graecanicam incipimus '). Fabulam Graecanicam - a Grecian fable: singular, not plural. This obviously refers to the main story of Lucius's transformation adapted from a Greek fable; making the plot of the ass primary. One suspects that Apuleius delighted in this seeming discrepany--though the Golden Ass turns out to be both a single fable and a series of tales woven together (a bit like the Christian 'mystery of the trinity' in its unity/plurality contradictions). Apuleius's abjuration to the reader to lector - 'be attentive' is quite right: only the attentive reader will be able to resolve the intricate mysteries of the Golden Ass. |

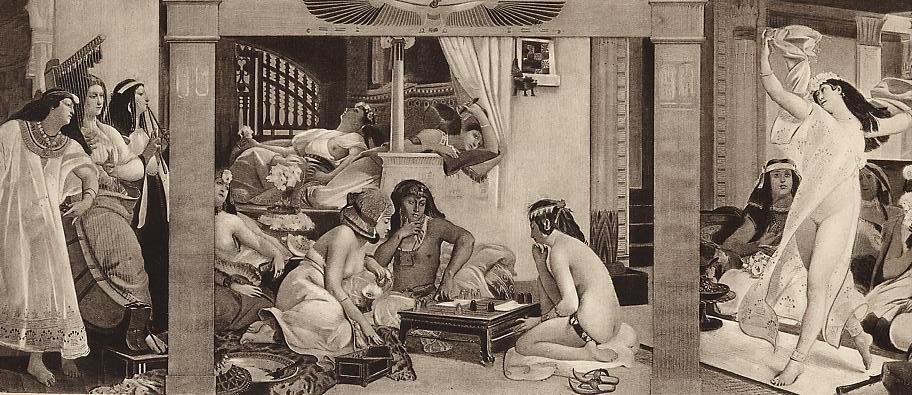

The Sphinx - painting

by Norman Lindsay (Jack Lindsay's father)

|

The Allegory of Lust (1540-50) [Venus & Cupid] painting by Bronzino |

At the centre of Apuleius's interweaving of tales is that of 'Cupid

and Psyche'. This tale--like the others--was not invented by Apuleius

either. The framework of the myth of 'Cupid and Psyche' is recurrent throughout

Indo-Aryan cultures, from Scotland to India. The best known version of

it is perhaps the Germanic fairy-story Cinderella. However, Apuleius's

retelling of this myth is an extraordinary feat of artistry--as P.G.

Walsh puts it, a transformation of a Märchen ('folk-tale')

into a Kunstmärchen ('Art-Story'). The eminent Victorian

aesthetic critic and essayist

Walter Pater

admired this section of the story so much that he included it in

its entirety in his book

Marius the Epicurean

(a study of the intellectual and spiritual development of a

young Roman in the time of Marcus Aurelius).

'Cupid and Psyche' is made by Apuleius to illuminate the larger whole of the Golden Ass, by being a reflection of the same theme. In this way, Apuleius projects the central thread of the tale of Lucius's transformation into the wider plane of mythos. As Lucius indulges his curiosity about Pamphile's witchcraft despite being repeatedly warned against doing so; so Psyche allows her curiosity to get the better of her, in spite of warnings parallel to those of Lucius. Both are punished by being forced to wander through the world, forsaken by all. Both are delivered from their misfortune through a series of trials--the labours of Venus in the case of Psyche, the serial stages of initiation into the mysteries of Isis for Lucius. Both stories seem at first blush to set up a division between 'appropriate' and 'forbidden' knowledge, with punishment afflicting those who dare to open the Pandora's box of the forbidden. However, it is overly hasty to extract such a moral from either of these tales. Psyche is eventually transported to Heaven and granted immortality; Lucius obtains an intimate relationship with the Goddess Isis. Neither Lucius nor Psyche would have attained the Divine in these parallel ways had they not first transgressed into the realm of illicit knowledge. Apuleius's Platonic philosophy is particularly evident in this episode, Cupid serving as an allegory of the soul's restless attempts to reach the Divine (Isis). As well, both tales show the same sort of bifurication of a Platonic ideal into a higher and a lower form, as expostulated by Apuleius in his Apologia [12]: 'But I will forbear to enlarge upon those deep and holy mysteries of the Platonic philosophy, which, while they are revealed to but few of the pious, are totally unknown to the profane; how, that Venus is a twofold goddess, each of the pair producing a particular passion, and in different kinds of lovers. One of them is the "Vulgar", who is prompted by the ordinary passion of love, to stimulate not only the human feelings, but even those of cattle and wild beasts, to lust, and commit the enslaved bodies of beings thus smitten by her to immoderate and furious embraces. The other is the "Heavenly" Venus, who presides over the purest love, who cares for men alone and but few of them, and who influences her devotees by no stimulants or allurements to base desire' (Bohn's trans. 258). It has been suggested that in this way two 'Cupids' compete for Psyche's love; and thar in the same way the 'higher Venus' prevails in the case of Lucius when Fotis is replaced by Isis. It does not seem clear that a relationship with both Isis and Fotis would be impossible for Lucius, however his attitude towards 'love' does seem change evolve from the lower Venus to the higher Venus in the course of the novel. |

|

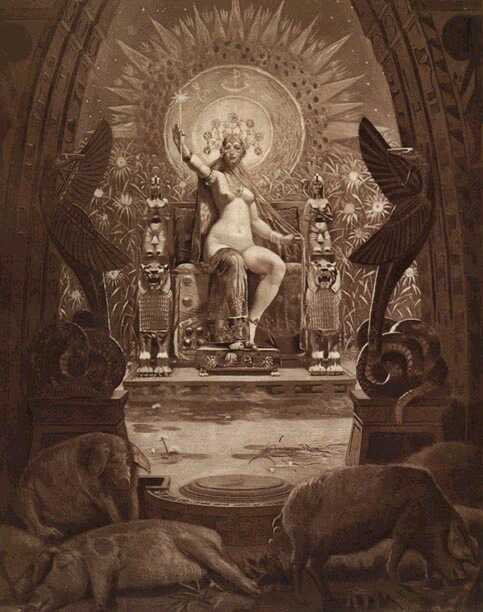

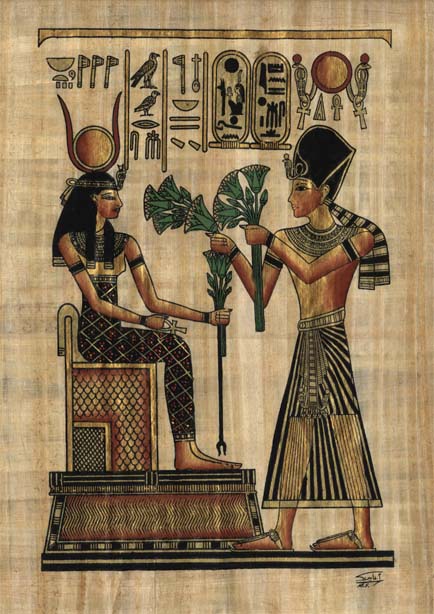

The solemn close of the Golden Ass--Lucius's initiation into the sacred rites of Isis and Osiris--may strike many readers as incongruous with the light-hearted style of the majority of the novel. This comes from the error of approaching the Golden Ass as purely a comic romance. Apuleius constructs a careful alternation between comic and tragic episodes, between romantic and dramatic. For instance, the comic encounter of Lucius and his miserly host Milo is offset by the tragic drama of the story of Socrates's death; the Lucius's romantic sexual encounters with the maidservant contrast with the horrifying story of Thelyphron's disfigurement he hears in the same book. Indeed, there are both comic-tragic and comic-romantic sections, as well as both dramatic-tragic and dramatic-romantic episodes. The Lucius-Fotis episodes, for example, could be termed comic-romantic; the Cupid-Psyche centre-story, dramatic-romantic. Lucius's transformation from man to ass is comic-tragic; while Charite's death is dramatic-tragic. In fact, the fates of Charite and Tlepolemus, Cupid and Psyche, and Lucius (and Fotis/Isis), are woven together in a complex counterpoint (what has been called the 'Charite-complex', see Schlam (1992)). For instance, the dramatic-tragic kidnapping of Charite in the fourth book complements Lucius's own capture by the dacoits; the romantic rescue of Charite in the seventh book is parallel to the finale of the 'Cupid & Psyche' story in the preceding books, and juxtaposed with Lucius's miserable experiences at the farms, also in the seventh book; Lucius's comic adventures with the priests contrast with Charite's tragic death in the eighth. All throughout, Apuleius alternates between jocular and often 'vulgar' happenings and 'high-brow' dramatic or tragic episodes. This is not dissimilar to the technique one observes in, for example, the tragedies of Shakespeare, which, as well as tragic elements, also contain humorous episodes; and are meant to be enjoyed on more than one level. Furthermore, there is a philosophic layer of the Golden Ass as well, as mentioned above, in the Platonic dualism between a lower, vulgar 'path' and a higher, heavenly 'path'; for instance, Venus competes for mastery over Lucius in her lower form as Fotis and her higher form as Isis (though, again, it is not clear that these two could not be reconciled, that is, that a relationship with Isis prevents Lucius from having a relationship with Fotis, though it certainly restricts the form of that relationship). One major theme of the narrative of Lucius in the Golden Ass, reflected in the tale of 'Cupid & Psyche', is this dualism of a debased and a perfected form of the same entity. Lucius is punished for his prurient curiosity into Pamphile's magic via his sexual liaison with Fotis by his transformation into a foolish ass. In the Apologia as well, Apuleius seeks to define healthy curiosity as that which endeavours towards knowledge of true reality by rational, intellectual means, as well as religious experience; as opposed to base curiosity which seeks an illusionary reality (Hindu 'maya ') by way of left-hand magic ('black magic') and undirected sensuality. As William Adlington said of the Golden Asse during his Introductory Address and Epistle Dedicatory, delivered from University College, Oxford on 18th September 1566: 'Although the matter therein seeme very light and merry, yet the effect thereof tendeth to a good and vertuous moral...under the wrap of this transformation is taxed the life of mortall men, when as we suffer our mindes so to bee drowned in the sensuall lusts of the flesh, and the beastly pleasure thereof...so can we never be restored to the right figure of ourselves except we taste and eat the sweet Rose of reason and vertue, which rather by the mediation of praier we may assuredly attaine'. As Robert Graves reports in his introduction, mid-20th century research into the history of magic and witchcraft has revealed that there were Thessalian witches who preserved a pre-Aryan tradition of destructive, 'left-hand' magic, associated with the Triple Moon-Goddess in her form of Hecate. The 'right-hand', benevolent magic is connected to the mysteries of Isis--the Goddess Lucius/Apuleius come to worship. Thus, the Golden Ass should not be read as containing a 'Puritan' moral of coverting sexual love into love of God, and the abandonment of magic in favour of 'religion'. Sensuality is not inherently vulgar, nor is magic always evil; both can take either a destructive, 'left-hand' character or a positive, 'right-hand' form--just as the Moon-Goddess appears both as Hecate and as Isis. Lucuis's form as an ass is also significant in terms of the philosophy of the Golden Ass. Though the title is typically thought to mean something like 'The Princes of All Ass-Stories' or 'The Best of Asses', there may be a purposeful ambiguity between the sense of aureus as meaning 'best' and its more literal meaning of 'golden'. Martin has suggested that the Latin title may translate the Greek ονος πυρρος "tawny ass" associated with the demon Typhon (as Plutarch details in his De Iside ). The worship of Isis in the form known to Apuleius and Plutarch actually arose in Greek and Roman days, Her Egyptian precursor Aset (the latter name written with the hieroglyphic for 'throne') having been almost completely forgotten for hundreds of years, and there being very few priests left who could even read the hieroglyphics on the temple walls. To continue, in Plutarch's account, briefly: Typhon (Seth in Egyptian) is the evil brother of the God King Osiris. Typhon contrived a plan to usurp his brother whereby he tricked Osiris into stepping into a heavily-ornamented box fitted exactly to his dimensions. No sooner had Osiris entered the box then Typhon had it nailed-shut and sealed with molten lead. He and his conspirators then threw this casket into the river. The pans & satyrs learn of this trick and inform Osiris's sister-wife, Isis. She searches all of the lands for the Osiris's coffin and, upon finding it, tears off the lid and carresses the dead face of Her beloved brother-husband. Her carresses turn more urgent until She begins to copulate with the cold body of Osiris (reminiscent of some representations the Hindu Goddess Kali astride the prostate, lifeless body of Shiva) and conceives a child, Horus. When Typhon learns of the body's discovery, he chops the body into tiny bits, casting them hither and yon through the lands. Isis retrives all of the parts, except for Osiris's male-member (symbolising his virility and strength), which Typhon cast into the river to be eaten by pikes (Egyptians traditionally avoided eating pike for this reason). However, Isis made a replica phallus and consecrated it--this event replicated in ceremonies performed by the ancient Egyptians in a festival (again, quite similar to the Hindu Shiva-lingam worshippers, particularly prevalent in the south of India). Later Horus, Osiris's truly post-humous son, overthrows the cruel Typhon. Because of Typhon's slaying of Her husband, the tawny ass of Typhon is particularly repellent to Isis, as She says to Lucius: '...de proximo clementer velut manum sacerdotis osculabundus rosis decerptis pessimae mihique iam dudum detestabilis belvae istius corio te protinus exue' (Apuleius XI.6)--'...when you have drawn near, make as if you intend to kiss the priest's hand, and gently detach the roses; at once then shrug off the skin of this most hateful of animals, which has long been abominable in my sight ' (Walsh trans. 221--my emphasis ). The owl, into which shape Pamphile transforms, on the other hand, is a symbol of wisdom, and the owl is thus often associated with Athena/Minerva . Isis's delieverance of Lucius, despite his being incarcerated in the form most hateful to Her, is particularly praiseworthy when viewed against the backdrop of the Egyptian myths associated with Isis & Osiris. |

Pharaoh Ramses presents Roses to Isis  Crete (1940) -

Crete (1940) - painting by Norman Lindsay (Jack Lindsay's father)

|

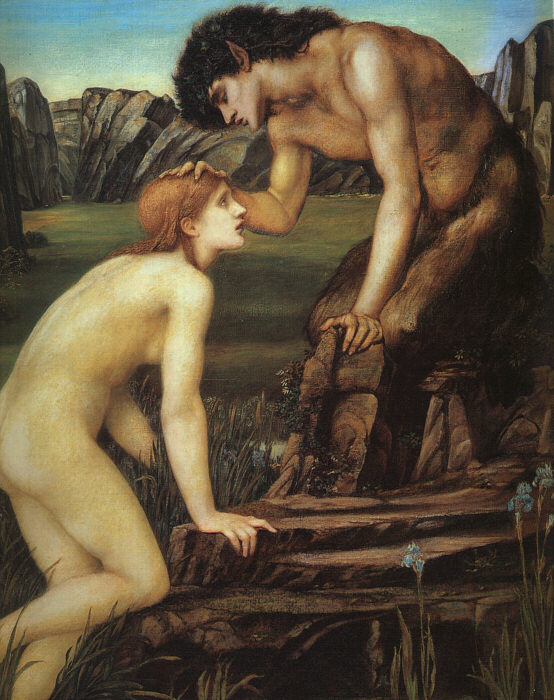

Pan comforts Psyche -

Pan comforts Psyche -painting by Sir Edward Burne-Jones |

Following Plutarch's De Iside et Osiride, Isis represents all that is well-ordered and beautiful in the world; Typhon chaos and irrationality. The priest's address to Lucius in the final book: 'Sed utcumque Fortunae caecitas, dum te pessimis periculis discruciat, ad religiosam istam beatitudinem inprovida produxit malitia' (Apuleius XI.15)--'But in spite of all, Fortune with her blind eyes, all the while that she was tormenting and cruelly imperilling you, has by the very exercise of her unforeseeing malignity brought you to this state of beautitude of release' (adapted from Walsh trans. 227). The lassitudes of irrationally cruel Fortune accidently bring Lucius into Isis's grace. Again, 'Fortune with blind eyes' is representative of disruptive Typhon, whose actions are unintelligibly cruel; as opposed to the rational order symbolises by Isis (note: this is a very different opposition from that of Apollonian order v. Dionysian chaos--as discussed in Nietzsche's Die Geburt der Tragödie ['The Birth of Tragedy']--where order and chaos are aligned quite differently, i.e. chaos with the primal, with music, &c. and order with the 'civilised', with sculpture, &c.). The ass in Apuleius's day therefore represented cruelty and lust; when Charite escapes from the dacoits and rides home on Lucius's back, Apuleius remarks that this is an extra-ordinary sight: 'virginem asino triumphantem ' (Apuleius VII.13). Literally, 'a virgin triumphantly riding an ass'; figuratively, 'purity dominating the lusts of the flesh without bit or bridle'. Further, Plutarch records an Egyptian festival in which asses and men dressed in Typhon's colours (tawny gold-red) were pushed over a cliff in ritualistic vengeance for Osiris's murder. Lucius's form as an ass may also be significant for another reason: Tertullian in his Apologeticus [37] reports in that some Africans believed that Christians's worshipped an ass's head ('somniastis caput asininum esse deum nostrum'). And that a condemned man in the amphitheatre guyed the Christian god by wearing ass's ears and a hoof. Tertullian suggests that this strange notion may have originated from a distortion of Jewish practices in Tacitus's Histories. If this is evidence of Apuleius's antagonism towards Christianity (and it is supported by his representation of the cruel wife of the baker in Book 9 as adhering to a faith with a deity whom she proclaimed to be the only god), then it is not surprising, given the probable situation of Christian propaganda being spread both in Rome and in North Africa during Apuleius's life. |

|

It is probable that Apuleius met with Christians and Christian-missionary texts whilst in Rome, one such apology by Marcianus Aristides is a nasty attack on Isiac religion (Isis-worship). And then, his return to Carthage co-incided with the burst of Christianity in North Africa--Madauros, his own birthplace, being one of the centre of Christian witness (Turtullian's reports are that all of Roman North Africa was in turmoil in the 190s due to the spread of Christianity). Thus, the Golden Ass--and Apuleius's rendering of the 'Cupid & Psyche' myth in particular--may be partially contrived as counter-doctrines to those of Christianity which Apuleius saw as threatening both the Isiac religion and Platonic philosophy. Thus his emphasis on the numen unicum multiformi specie (Apuleius XI.5), or 'single godhead with manifold forms' of Isis. In the middle ages, the Inquisition, not surprising, attempted to destroy all known editions of Apuleius's work due to its jabs at Christianity and Christians, such as the portrayal of the baker's wife, one of the wickest characters in the novel: 'Tunc spretis atque calcatis divinis numinibus in viceram certae religionis mentita sacrilega praesumptione dei, quem praedicaret unicum, confictis observationibus vacuis fallens omnis homines et miserum maritum decipiens matutino mero et continuo corpus manciparat' (Apuleius IX.14) ['She scorned and spurned the gods of heaven; and in the place of true religion she professed some fantastic blasphemous creed of a God whom she named the One and Only God. But she used her deluded and ridiculuous observances chiefly to deceive the onlooker and to diddle her wretched husband; for she spent the morning in boozing, and leased out her body in perpetual prostitution' (Lindsay trans. 276) The baker's wife is further described by Apuleius as 'saeva scaeva viriosa ebriosa pervicax pertinax' (Apuleius IX.14), which provides a good example of Apuleius's rich, musical style of Latin prose--here combining both rhyme and alliteration. Such phrases illustrate the immense challenge for translators of the novel, if they are to attempt to preserve both the meaning and the form of the original to any degree. Some abandon any try at replicating the phonic-form, reading 'mischievous, malignant, addicted to men and to wine, froward and stubborn' (Bohn's ed. trans. 175), 'crabbed, cruell, lascivious, drunken, obstinate, niggish' (Adlington trans. 209), 'malicious, cruel, spiteful, lecherous, drunken, selfish, obstinate' (Graves trans. 203). Other translators use quite a variety of verbal tricks to get at the rhythm of the original, and succeed to varying degrees: 'crabbed and crotchety, libidinous and bibulous, obdurate and obstinate' (Walsh trans. 170), 'hard-hearted, perverse, man-mad, drunken, and stubborn to the last degree' (Kenney trans. 154), 'lewd and crude, a toper and a groper, a nagging hag of a fool of a mule' (Lindsay trans. 276). Apuleius has a liking for outlandish and bizarre expressions and tangles the archaic with the colloquial in a disorienting mélange. But it is this very exotic elixir of his language which sets the right tone for his tale of mingled drama and comedy, chivalrous love and comic lust. One should not be mislead by his apologies for his poor Latin: 'Mox in urbe Latia advena studiorum Quiritium indigenam sermonem aerumnabili labore nullo magistro praeeunte aggressus excolui. En ecce praefamur veniam, siquid exotici ac forensis sermonis rudis locutor offendero. Iam haec equidem ipsa vocis immutatio desultoriae scientiae stilo quem accessimus respondet. Fabulam Graecanicam incipimus.' (Apuleius I.1) ['Later in Rome, as a stranger to the literary pursuits of the citizens there, I tackled and cultivated the native language without the guidance of a teacher, and with excruciating difficulty. So at the outset I beg your indulgence for any mistakes which I make as a novice in the foreign language in use at the Roman bar. In fact this linguistic metamorphosis suits the style of the writing I have adopted here--the same sort of trick, you might say, as that employed by a circus-rider who leaps from one horse to another--for the romance on which I am embarking is adapted from the Greek' (trans. adapted from those of Walsh & Kenney, pp. 1 & 7, resp.)] Like his circus-rider, Apuleius has pulled a trick here, in switching from the horse of begging apology to that of insinuating that a Greek might be able to teach the Romans a thing or two about their own tongue. And indeed, the prose following this prologue is not only unique and wonderful in its content, but also in its linguistic form. |

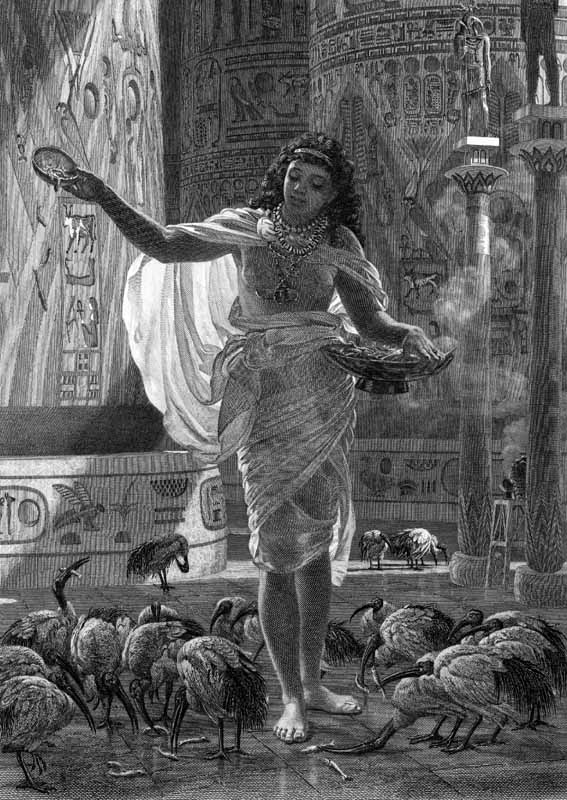

Feeding the Sacred Ibis - an engraving of a painting by E. J. Poynter |

Please do not reproduce any of the text above/herein

without permission from the author

and/or proper citation.

(your professors will know if you do!)

(your professors will know if you do!)

References

Apuleius. Apulei Platonici Madaurensis

Metamorphoseon Libri XI (Apulei Opera Quae Supersunt,

vol I). edition

& commentary by Rudulfus Helm.

Leipzig: Bibliotheca Teubneriana, 1907.

Apuleius. The Golden Ass. translation, notes, preface by Jack Lindsay. illustrated by Percival Goodman. New York: The Limited Editions Club, 1932.

Apuleius. The Golden Ass. translation, notes, preface by P.G. Walsh. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999 (1994).

Apuleius. The Golden Ass or Metamorphoses. translation, notes, preface by E.J. Kenney. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1998.

Apuleius. The Golden Asse. translation, notes by William Adlington. preface by E.B. Osborn. illustrated by Jean de Bosschère. London: John Lane - The Bodley Head, 1923.

Apuleius. The Transformations of Lucius, otherwise known as The Golden Ass. translation, notes by Robert Graves. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2000 (1950).

Apuleius. The Marriage of Cupid and Psyche. translation by Walter Pater. illustrated by Edmund Dulac. originally printed as part of the novel Marius the Epicurean .

London: Macmillan, 1885 . (reprinted, Norwalk, Connecticut: The Heritage Press, 1951.)

Apuleius. The Works of Apuleius, comprising The Metamorphoses, or Golden Ass, The God of Socrates, The Florida and His Defence, or a Discourse on

Magic (a new translation); to which are added, A Metrical Version of Cupid and Psyche and Mrs. Tighe's Psyche (a Poem in six Cantos). translation, notes,

preface by unknown. Bohn's Libraries. London: George Bell & Sons, 1902.

Lucian. True History and Lucius or the Ass. translation, preface by Paul Turner. illustrated by Hellmuth Weissenborn. Bloomington: Indiana Uni. Press, 1958.

Mahabharata.translation & preface by Kamala Subramaniam. Bombay: Bharatya Vidya Bhavan, 1997 (1965).

Martin, René. 'Le sens de l'expression asinus aureus et la signification du roman apuléien.' Revue des études latines 48 (1970), pp. 332-354.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. Die Geburt der Tragödie aus dem Geiste der Musik. Leipzig: E. W. Fritzsch, 1872.

Petersson, Margareta. Unending Metamorphoses: Myth, Satire and Religion in Salman Rushdie's Novels. Lund: Lund Uni. Press, 1996.

Plutarch. 'On Isis and Osiris'. in Moralia V. translation, notes, preface by Frank C. Babbit. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Uni. Press, 1936.

Schlam, Carl C. The Metamorphoses of Apuleius: on making an ass of oneself. Chapel Hill: Uni. of North Carolina Press, 1992.

Walsh, P. G. 'Apuleius and Plutarch'. in Neoplatonism and Early Christian Thought: essays in honour of A. H. Armstrong. H. J. Blumenthal & R. A. Markus (eds.).

London: Variorum, 1981, pp. 20-32, 256.

The Golden Ass ONLINE--

complete Latin & English editions:

Leipzig: Bibliotheca Teubneriana, 1907.

Apuleius. The Golden Ass. translation, notes, preface by Jack Lindsay. illustrated by Percival Goodman. New York: The Limited Editions Club, 1932.

Apuleius. The Golden Ass. translation, notes, preface by P.G. Walsh. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999 (1994).

Apuleius. The Golden Ass or Metamorphoses. translation, notes, preface by E.J. Kenney. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1998.

Apuleius. The Golden Asse. translation, notes by William Adlington. preface by E.B. Osborn. illustrated by Jean de Bosschère. London: John Lane - The Bodley Head, 1923.

Apuleius. The Transformations of Lucius, otherwise known as The Golden Ass. translation, notes by Robert Graves. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2000 (1950).

Apuleius. The Marriage of Cupid and Psyche. translation by Walter Pater. illustrated by Edmund Dulac. originally printed as part of the novel Marius the Epicurean .

London: Macmillan, 1885 . (reprinted, Norwalk, Connecticut: The Heritage Press, 1951.)

Apuleius. The Works of Apuleius, comprising The Metamorphoses, or Golden Ass, The God of Socrates, The Florida and His Defence, or a Discourse on

Magic (a new translation); to which are added, A Metrical Version of Cupid and Psyche and Mrs. Tighe's Psyche (a Poem in six Cantos). translation, notes,

preface by unknown. Bohn's Libraries. London: George Bell & Sons, 1902.

Lucian. True History and Lucius or the Ass. translation, preface by Paul Turner. illustrated by Hellmuth Weissenborn. Bloomington: Indiana Uni. Press, 1958.

Mahabharata.translation & preface by Kamala Subramaniam. Bombay: Bharatya Vidya Bhavan, 1997 (1965).

Martin, René. 'Le sens de l'expression asinus aureus et la signification du roman apuléien.' Revue des études latines 48 (1970), pp. 332-354.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. Die Geburt der Tragödie aus dem Geiste der Musik. Leipzig: E. W. Fritzsch, 1872.

Petersson, Margareta. Unending Metamorphoses: Myth, Satire and Religion in Salman Rushdie's Novels. Lund: Lund Uni. Press, 1996.

Plutarch. 'On Isis and Osiris'. in Moralia V. translation, notes, preface by Frank C. Babbit. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Uni. Press, 1936.

Schlam, Carl C. The Metamorphoses of Apuleius: on making an ass of oneself. Chapel Hill: Uni. of North Carolina Press, 1992.

Walsh, P. G. 'Apuleius and Plutarch'. in Neoplatonism and Early Christian Thought: essays in honour of A. H. Armstrong. H. J. Blumenthal & R. A. Markus (eds.).

London: Variorum, 1981, pp. 20-32, 256.

The Golden Ass ONLINE--

complete Latin & English editions:

|

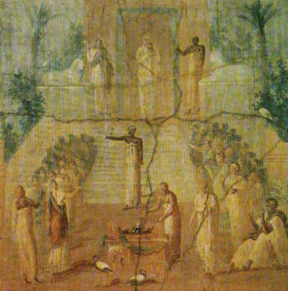

wall-painting

from Pompeii showing the rituals of the cult of Isis

|

APULEIUS'S GOLDEN ASS

**COMPLETE ENGLISH text ONLINE ** (Adlington's translation of 1566, 'published' on the web by Martin Guy, with a glossary)

Psyche Entering Cupid's Garden - painting by John William Waterhouse |

The Golden Ass :

Editions, Translations,

Textual Comparisons of Selected Passages

+ Links to Book Sellers

[click here!]

title-page from John Price's Latin edition

of 1650 (Gouda)

read selected

passages from different translations alongside of Latin original;

information on translators & translations;

find & buy your favourite edition of the Golden Ass!

find & buy your favourite edition of the Golden Ass!

an ass just

outside of Madaura (Algeria)

an ass just

outside of Madaura (Algeria)